First transmitted 4th October 1981

|

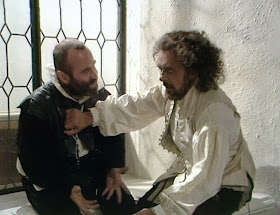

Bob Hoskins provokes the green-eyed monster in Antony Hopkins |

Cast:

Anthony Hopkins (Othello), Bob Hoskins (Iago), Penelope Wilton (Desdemona),

Rosemary Leach (Emilia), David Yelland (Cassio), Geoffrey Chater (Brabantio),

John Barron (Duke of Venice), Joseph O’Conor (Lodovico), Anthony Pedley

(Roderigo), Tony Steedman (Montano), Wendy Morgan (Bianca)

Director: Jonathan Miller

Well there is no escaping it really. The picture above says

it all. This production comes from a different time – a time when it was not

seen as an unspeakable possibility that a white actor should don the facepaint

and boot polish to play theatre’s most famous moor. So let’s tackle that issue

first shall we?

Well there is no escaping it really. The picture above says

it all. This production comes from a different time – a time when it was not

seen as an unspeakable possibility that a white actor should don the facepaint

and boot polish to play theatre’s most famous moor. So let’s tackle that issue

first shall we?

For starters, it was not the original intention. Cedric

Messina had originally intended to feature Othello

in his plans for the second season of Shakespeare productions. He had the

perfect actor lined up: James Earl Jones. A respected and well established

Broadway star, Jones would have brought a real touch of Hollywood glamour to

the series. Unfortunately, in the eyes of Equity he was guilty of an

unpardonable fault: he was American. And, damn it, this was a British series

that was there to give jobs for British actors – so why should this peach of a

role go to some Yankee? So Jones was denied a visa to work on the series – and

the production was placed on stand-by.

Enter Jonathan Miller. With no Jones, Miller announced, in

his opinion, the play was less about race anyway, more about jealousy and envy.

Miller had been one of the few openly critical of Olivier’s casting as Othello

in the 60s and also believed Othello was an Arab rather than the African he was

so often played as. As such, he focused on picking the best actor and avoiding

playing up any racial characteristics in the performance. Of course you could

criticise him (clearly) for not identifying a prominent black or Arabic classical

actor – but the fact is a cursory glance at the RSC at the time shows he would

not have been spoilt for choice in the 1970s. Hugh Quashie (later to appear in

the series as a very different moor, Aaron) would have been the obvious choice

– and would have given a very fine performance – but this time the election

fell on Hopkins.

Hopkins does acquit himself well. Recent memories abound of

scenery consuming roles in Hollywood films, but his Othello is a softly spoken,

very controlled man, who has worked hard to integrate himself into his society

– more Venetian than the Venetians. From his first scene, he is calm, rational,

gentle and amused at the thought of threat or physical danger. It’s a very

conscious absorbing of nobility, his calm assurance notable in a A1 S3 as he

leans gently on the council table to tell the particulars of his wooing of

Desdemona, smiling and with glances almost daring Brabantio to contradict him.

When banishing Cassio, he stands quietly assured, hiding his fury.

Hopkins does acquit himself well. Recent memories abound of

scenery consuming roles in Hollywood films, but his Othello is a softly spoken,

very controlled man, who has worked hard to integrate himself into his society

– more Venetian than the Venetians. From his first scene, he is calm, rational,

gentle and amused at the thought of threat or physical danger. It’s a very

conscious absorbing of nobility, his calm assurance notable in a A1 S3 as he

leans gently on the council table to tell the particulars of his wooing of

Desdemona, smiling and with glances almost daring Brabantio to contradict him.

When banishing Cassio, he stands quietly assured, hiding his fury.

The aim of Iago is to break down this controlled exterior to

reveal the rage beneath. The one area where this man falls down is his almost

childlike innocence in love. There is a boyishness in Othello – he playfully

wrestles Iago to the floor when arriving in Cyprus – that extends to the chasteness

of his relationship with his wife. Their kisses are brief and gentle, almost as

if they are waiting to be told off. He seems almost in awe of her – the look on

his face when she leaves him in A3 S3 (before Iago goes to work) is almost akin

to worship. It hints at a deeper insecurity: as if he cannot believe that he, a

stranger in Venetian society, could be loved by such a woman.

What a contrast then to the man destroyed by Iago! A3 S3 is

a bravura scene of acting and direction (as is his custom, Miller uses many

long takes to allow the performances to develop during the scene) and it

deconstructs and rebuilds Othello into a man much wilder – almost bestial – than

the calmer figure before. The scene is a slow descent: first he is sharper,

pointedly stating “she chose me”, making a show of relaxing, of avoiding Iago.

From there he becomes more emotional, tearful before ripping into a violent

outburst, wild-haired and wild-eyed screaming, like a temper tantrum. It’s a

note Hopkins carries forward, a man unbalanced by his passions, who strikes Desdemona

one moment, then weepingly seems to be looking for the comfort he once had from

her, but without being able to confess what concerns him.

What a contrast then to the man destroyed by Iago! A3 S3 is

a bravura scene of acting and direction (as is his custom, Miller uses many

long takes to allow the performances to develop during the scene) and it

deconstructs and rebuilds Othello into a man much wilder – almost bestial – than

the calmer figure before. The scene is a slow descent: first he is sharper,

pointedly stating “she chose me”, making a show of relaxing, of avoiding Iago.

From there he becomes more emotional, tearful before ripping into a violent

outburst, wild-haired and wild-eyed screaming, like a temper tantrum. It’s a

note Hopkins carries forward, a man unbalanced by his passions, who strikes Desdemona

one moment, then weepingly seems to be looking for the comfort he once had from

her, but without being able to confess what concerns him.  His calmness only returns when he is once again given a

purpose – her murder. Their dialogue before the murder could almost be a normal

married argument, before his rage is unleashed – Penelope Wilton’s head-girl

manner, from Othello’s perspective, her air of unimpeachable openness makes her

betrayal far worse. Hopkins probably goes too far here with his maddened stare

into the camera as he smothers her. After the death, he is a broken-hearted boy

once more – and only returns to his regal manner after Iago’s villainy is

revealed and he has a new duty – suicide. It’s a rich, complex performance, in

no way a racial stereotype, but a great actor using the tools of his trade to

utmost effect. Where it is perhaps weaker is in the moments of rage – Hopkins

comes across at these points too theatrically. But the quieter moments are

triumphs of filmic technique.

His calmness only returns when he is once again given a

purpose – her murder. Their dialogue before the murder could almost be a normal

married argument, before his rage is unleashed – Penelope Wilton’s head-girl

manner, from Othello’s perspective, her air of unimpeachable openness makes her

betrayal far worse. Hopkins probably goes too far here with his maddened stare

into the camera as he smothers her. After the death, he is a broken-hearted boy

once more – and only returns to his regal manner after Iago’s villainy is

revealed and he has a new duty – suicide. It’s a rich, complex performance, in

no way a racial stereotype, but a great actor using the tools of his trade to

utmost effect. Where it is perhaps weaker is in the moments of rage – Hopkins

comes across at these points too theatrically. But the quieter moments are

triumphs of filmic technique.

The real gem of the performance here however is Bob Hoskins.

Has there been a finer performance of Iago captured on film? Hoskins certainly

must stand up there with the greatest performances of this role of all time.

His Iago is a playfully destructive figure, playing with lighted flames when he

is alone, throwing water at Brabantio in the middle of gulling the man.

Hoskins’ performance is a triumph of conveying inspiration – his soliloquies

and asides showcase his ability to act ‘thinking’ before the camera, making it

clear he is as uncertain about the next step he will take as anyone else.

There are several lovely moments of improvisation: in a

particularly brilliant touch, in A4 S1 he leads Othello into the bedroom to

point at the bed “she has contaminated”, clearly seizing inspiration for a

suitable place for the murder. This improvisation is two-sided. He doesn’t

think through implications (either because he can’t or he doesn’t care) and hands

over damning letters about him from Roderigo’s corpse. He’s like a shark – only

able to power forward and with very little thought about his eventual

destination, seizing opportunities as they land in front of him. Momentum is

his main weapon – Miller makes it clear that a simple pause and drawing of

breath from the other characters would be enough to shatter his plans – making

the events in many ways even more tragic.

There are several lovely moments of improvisation: in a

particularly brilliant touch, in A4 S1 he leads Othello into the bedroom to

point at the bed “she has contaminated”, clearly seizing inspiration for a

suitable place for the murder. This improvisation is two-sided. He doesn’t

think through implications (either because he can’t or he doesn’t care) and hands

over damning letters about him from Roderigo’s corpse. He’s like a shark – only

able to power forward and with very little thought about his eventual

destination, seizing opportunities as they land in front of him. Momentum is

his main weapon – Miller makes it clear that a simple pause and drawing of

breath from the other characters would be enough to shatter his plans – making

the events in many ways even more tragic.

Miller also uses Hoskins’ working-class roots as a strength

– Iago here is a natural NCO, trusted by everyone as much because he is a

‘simple soldier’ among his betters. Hoskins never seems to stop smiling, his

unaffected accent and bluntness signs to everyone else of his trustworthiness.

Hoskins’ whole performance is a triumph of marrying up the many different

images both the characters and the audience have of Iago – and in making it

understandable why so many are fooled by him.

Iago’s instability is also to the fore. If Othello is a

head-boy, Iago is a destructive tearaway, giggling delightedly at the slightest

provocation (this giggling runs throughout the whole play, heightened during

the murder of Roderigo, and he disintegrates into nothing but giggles by the

play’s end). His psychotic nature is hidden by his constant ingratiation –

Miller continually frames him on the left of the shot, often looking up at the

face of the man he is manipulating, his face close, his voice calm and

reasonable. He’s a different man for each character, but each personality is on

the surface deferential – from his Sancho Panza to Roderigo, to his humble

batman to Lodovico.

Miller’s work also demonstrates the close-bonds between Othello

and Iago. Othello shows more comfort in physical contact with Iago than he ever

does with Desdemona – Iago tenderly fixes his uniform, and the two of them

wrestle playfully at several points. When spinning his lies, Iago takes Othello

in a bear hug, and then an embrace/headlock (there are hints that Iago is even

a little shocked at the emotion he has provoked from Othello) of a kneeling

Othello. While Othello is controlled, calm and rational, Iago presents himself

as jolly, open and likeable – but his psychotic anger under the surface is

reflected in the murderous rage he unleashes in Othello. They make a fantastic

partnership.

Miller’s work also demonstrates the close-bonds between Othello

and Iago. Othello shows more comfort in physical contact with Iago than he ever

does with Desdemona – Iago tenderly fixes his uniform, and the two of them

wrestle playfully at several points. When spinning his lies, Iago takes Othello

in a bear hug, and then an embrace/headlock (there are hints that Iago is even

a little shocked at the emotion he has provoked from Othello) of a kneeling

Othello. While Othello is controlled, calm and rational, Iago presents himself

as jolly, open and likeable – but his psychotic anger under the surface is

reflected in the murderous rage he unleashes in Othello. They make a fantastic

partnership. There is room for other performances as well, of course.

Penelope Wilton’s Desdemona has a head-girlish prissiness, and is a woman who

has lived an entirely open and honest life, devoid (until now) of any rebellion.

She seems very innocent sexually (much like her husband), and earnestly wants

to do the right thing. This characterisation is great at pointing up her

helplessness and emotional upset at Othello’s behaviour – clearly having no

idea what she has done. Her inward grief is very well played throughout –

particularly in the (often cut) A4 S3 where her quiet sadness and helplessness

is very affecting. Like Othello, she seems naïve and slightly adrift in the

adult world – only at her death does she finally shy away from her gentleness

towards anger and outrage at her treatment, though Wilton is careful never to

suggest any compromise in her feelings.

There is room for other performances as well, of course.

Penelope Wilton’s Desdemona has a head-girlish prissiness, and is a woman who

has lived an entirely open and honest life, devoid (until now) of any rebellion.

She seems very innocent sexually (much like her husband), and earnestly wants

to do the right thing. This characterisation is great at pointing up her

helplessness and emotional upset at Othello’s behaviour – clearly having no

idea what she has done. Her inward grief is very well played throughout –

particularly in the (often cut) A4 S3 where her quiet sadness and helplessness

is very affecting. Like Othello, she seems naïve and slightly adrift in the

adult world – only at her death does she finally shy away from her gentleness

towards anger and outrage at her treatment, though Wilton is careful never to

suggest any compromise in her feelings.

Rosemary Leach gives a stirring performance in the

scene-stealing role of Emilia, fiercely loyal and protective of those she loves

and willing to stand for what she believes in. Anthony Pedley produces another

strong performance in the series as an out-of-his-depth Roderigo, an aristocrat

who never sees betrayal coming from a friend. David Yelland makes a wonderfully

cool (and therefore suspicious) Cassio (his heartlessness towards Wendy

Morgan’s needy Bianca is also a very nice touch). Geoffrey Chater and John

Barron were both a little too broad or sing-song for my taste, although Tony

Steedman and Joseph O’Conor make strong impressions in the smaller parts.

Miller’s direction is, as always, intelligent and

illuminates small moments. Visual inspiration comes from Velazquez, while the

set-design (essentially a long corridor of inter-connecting rooms) successfully

uses the scale of television to focus the production as a claustrophobic

chamber piece. His use of long takes is very successful, particularly in the

main Iago/Othello scenes, as it gives the actors room to develop the scene

naturally within shot. This is possibly the most performance-central production

so far, focused by the fact that this play is almost a four-hander with only

2-3 other major characters, the smallest cast of any of the great tragedies.

Miller’s direction is, as always, intelligent and

illuminates small moments. Visual inspiration comes from Velazquez, while the

set-design (essentially a long corridor of inter-connecting rooms) successfully

uses the scale of television to focus the production as a claustrophobic

chamber piece. His use of long takes is very successful, particularly in the

main Iago/Othello scenes, as it gives the actors room to develop the scene

naturally within shot. This is possibly the most performance-central production

so far, focused by the fact that this play is almost a four-hander with only

2-3 other major characters, the smallest cast of any of the great tragedies.

Technically there are also some beautiful images here –

lighting during the two contrasting dinner scenes is lovely – and Miller

introduces many small touches, from Iago’s water antics at the opening to

Othello performing magic tricks to amuse his guests. The murder of Roderigo

takes place in a Third Man-style

series of cloisters. He does sometimes overplay his hand visually: the

prominent skull that sits on a table opposite Desdemona in an otherwise

wonderfully played A4 S3 is perhaps a bit much.

I’ve already written a lot about Othello/Iago in this

production, but Miller does manage to front-and-centre the theme of jealousy

and envy, as well as the dangers of blind trust very successfully. With Hoskins

he creates a demonic dwarf, who is vindictive rather than scheming. With Hopkins

he creates an Othello, imposing and dignified in his comfort zone, naïve and

lost outside it. What he does most successfully is present the characters and

situation in such a way that you would believe these events would unfold like

this. Cassio is cold enough to suggest he would betray Othello; Desdemona is

calm and, for want of a better word, British enough to avoid confronting

Othello until it is too late. Long takes hammer home the short timespan of the

play (it feels almost ‘real time’), while the simple black and white design and

costumes serve as a nice contrast to the far-from black-and-white story Iago is

creating.

I’ve already written a lot about Othello/Iago in this

production, but Miller does manage to front-and-centre the theme of jealousy

and envy, as well as the dangers of blind trust very successfully. With Hoskins

he creates a demonic dwarf, who is vindictive rather than scheming. With Hopkins

he creates an Othello, imposing and dignified in his comfort zone, naïve and

lost outside it. What he does most successfully is present the characters and

situation in such a way that you would believe these events would unfold like

this. Cassio is cold enough to suggest he would betray Othello; Desdemona is

calm and, for want of a better word, British enough to avoid confronting

Othello until it is too late. Long takes hammer home the short timespan of the

play (it feels almost ‘real time’), while the simple black and white design and

costumes serve as a nice contrast to the far-from black-and-white story Iago is

creating.

Miller also uses filming to enforce the manipulation. Framing repeatedly places Iago on the left of the frame, adding a visual consistency to his manipulation (strikingly he moves completely to the right for the final scene). In a daring sequence for a series based on placing text at the centre, he continues his experiments from Timon with deliberately making some of the dialogue inaudible to allow the viewer to feel some of the character isolation: in particular when Othello overhears Cassio 'confess' in A4 S1, he is placed behind the door with the camera with him - leaving us struggling to hear what is being said as much as Othello does (this infuriated some critics but is a lovely touch).

If there is a problem here, it’s got to come back to length

– this is the longest production so far, and although that is partly Shakespeare’s

fault, it’s tough on the bum. Miller sometimes I feel has so many good ideas

and points he wants to explore that he finds it impossible to leave any of them

out – combine this with the brief to avoid cutting, and you end up with

something that you need a couple of sittings to get through. But then when

there is such good stuff here as there is, it’s well worth the effort.

Conclusion

A good performance by Hopkins (despite the controversy) is

overshadowed by a rip-roaring turn by Hoskins, who turns this into the Iago

show – and gives one of the strongest turns of the series so far. Miller is

full of ideas and invention as always, and brings the focus very much onto the

leading characters, using moments of invention in performance to highlight their

natures. It’s overlong and, yes, it does take a bit of getting used to seeing

Hopkins black-up – but I’ve seen this production twice and it’s imaginative,

enlightening and highly enjoyable – and also succeeds in making a familiar

story sad and moving.

King Lear (For Fun) thank you.

ReplyDelete

ReplyDeleteyummyladies.com support@yummyladies.com