First Broadcast 27th February 1980

|

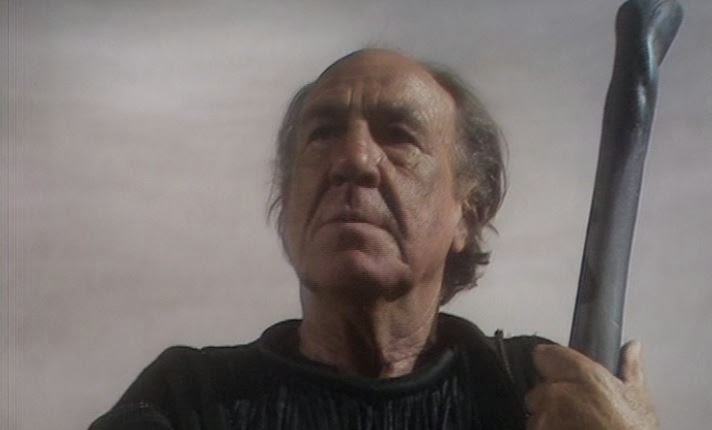

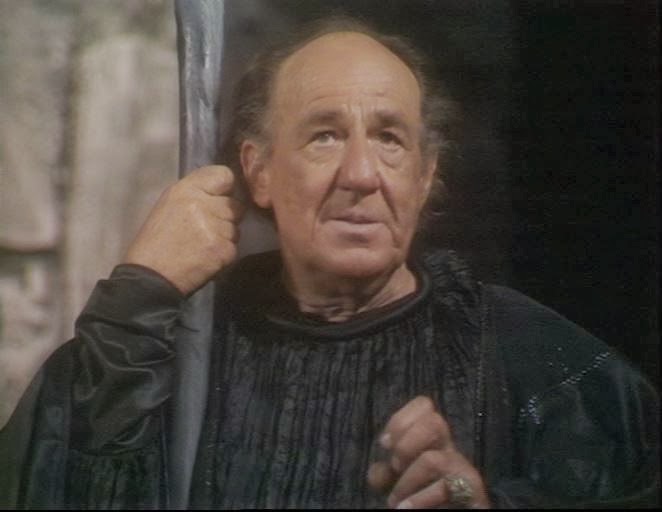

Michael Hordern opens graves at his command in The Tempest

|

Cast:

Michael Hordern (Prospero), David Dixon (Ariel), Pippa Guard (Miranda),

Christopher Guard (Ferdinand), Warren Clarke (Caliban), Nigel Hawthorne

(Stephano), Andrew Sachs (Trinculo), David Waller (Alonso), John Nettleton

(Gonzalo), Derek Godfrey (Antonio), Alan Rowe (Sebastian)

Director: David Gorrie

I’ve

always found The Tempest a strange

piece of theatre. In some ways it’s a very tightly structured piece of work –

Act 1 introduces all the characters; Acts 2 and 3 split them into clear

groupings with two scenes for each (Prospero/Miranda/Ferdinand, the shipwrecked

lords, Stephano/Trinculo/Caliban – with only Ariel moving between these

matchings); Act 4 draws them back together in one long scene with Prospero and

Ariel pulling the strings; and Act 5, in another long scene, ties everything up

in a neat bow. It’s the only Shakespeare play I can think of that balances

three simultaneous plotlines like this, and the economy with which it is done

points out the Bard’s strengths as a narrative structuralist – something I

think that often gets missed (not least because many of the plays are at point

flabbily structured).

I’ve

always found The Tempest a strange

piece of theatre. In some ways it’s a very tightly structured piece of work –

Act 1 introduces all the characters; Acts 2 and 3 split them into clear

groupings with two scenes for each (Prospero/Miranda/Ferdinand, the shipwrecked

lords, Stephano/Trinculo/Caliban – with only Ariel moving between these

matchings); Act 4 draws them back together in one long scene with Prospero and

Ariel pulling the strings; and Act 5, in another long scene, ties everything up

in a neat bow. It’s the only Shakespeare play I can think of that balances

three simultaneous plotlines like this, and the economy with which it is done

points out the Bard’s strengths as a narrative structuralist – something I

think that often gets missed (not least because many of the plays are at point

flabbily structured).

Now

I think this bow is all too neat, but this is probably related to the fact I

have twice played Antonio and never

really felt I found a convincing reason for why he accepts losing his Dukedom,

and I always found it puzzling that he offers no lines in the final scene to

Prospero (not even to say sorry!) and falls back on cheap cracks about Caliban

looking like a fish. However, that is a very personal note about this play. For

the record I think Derek Godfrey does a decent job here, though he and

Sebastian sometimes seem more like a pair of bitchy whiners than would-be

murderers. But that’s partly Shakespeare’s fault.

In

other ways this is a bizarre, almost dreamlike play with constant questions

over whether what we are seeing is even real, strange inconsistencies in time

(Ferdinand seems to have been labouring for days but only hours seem to go by

for Stephano and Trinculo), and a vague message about forgiveness threaded

through the play (although in other ways Prospero is quite the bully and

tyrant). As with As You Like It,

Shakespeare is playing with the ideas of theatricality by creating a

non-realist dreamlike world, perhaps a tip of the hat to the fact that the

Globe theatre company could never have created the actual island setting (and

storm) that the play demands.

Now

I think this bow is all too neat, but this is probably related to the fact I

have twice played Antonio and never

really felt I found a convincing reason for why he accepts losing his Dukedom,

and I always found it puzzling that he offers no lines in the final scene to

Prospero (not even to say sorry!) and falls back on cheap cracks about Caliban

looking like a fish. However, that is a very personal note about this play. For

the record I think Derek Godfrey does a decent job here, though he and

Sebastian sometimes seem more like a pair of bitchy whiners than would-be

murderers. But that’s partly Shakespeare’s fault.

In

other ways this is a bizarre, almost dreamlike play with constant questions

over whether what we are seeing is even real, strange inconsistencies in time

(Ferdinand seems to have been labouring for days but only hours seem to go by

for Stephano and Trinculo), and a vague message about forgiveness threaded

through the play (although in other ways Prospero is quite the bully and

tyrant). As with As You Like It,

Shakespeare is playing with the ideas of theatricality by creating a

non-realist dreamlike world, perhaps a tip of the hat to the fact that the

Globe theatre company could never have created the actual island setting (and

storm) that the play demands.

So creating

the island in a TV studio should really work, right? Well no. Because again the

set is an earnest attempt at creating a “real” location, but rather than going

with bright colours and suggestions of a location on a budget, this island is a

glum, muddy, shabby-looking papier-mache island, with the obligatory rocks,

bushes and birdsong soundtrack, and so overlit that it appears as artificial

and unmagical as possible. It’s all part of a painful earnestness around John

Gorrie’s production that experiments with magic and special effects at certain

moments, but settles for men in tights trudging around a fake beach. It’s flat

and lifeless throughout and lacking in colour in every sense. Every scene is

flatly shot from an “audience” prospective with no attempt made to exploit any

of the potential visual interest of the rocky outcrops that form Prospero’s

shelter.

So creating

the island in a TV studio should really work, right? Well no. Because again the

set is an earnest attempt at creating a “real” location, but rather than going

with bright colours and suggestions of a location on a budget, this island is a

glum, muddy, shabby-looking papier-mache island, with the obligatory rocks,

bushes and birdsong soundtrack, and so overlit that it appears as artificial

and unmagical as possible. It’s all part of a painful earnestness around John

Gorrie’s production that experiments with magic and special effects at certain

moments, but settles for men in tights trudging around a fake beach. It’s flat

and lifeless throughout and lacking in colour in every sense. Every scene is

flatly shot from an “audience” prospective with no attempt made to exploit any

of the potential visual interest of the rocky outcrops that form Prospero’s

shelter.

As

a director, John Gorrie seems at a loss with what to do here with the play,

totally lacking the strong sense of place, narrative drive and visual style

that he brought to Twelfth Night.

This is clear throughout his failure to really exploit the special effects and

editing tricks that TV has available to it. David Dixon’s Ariel disappears into

thin air a few times (usually after a run and jump) and can be seen as a

transparent spirit but that’s about it. He still moves normally (editing isn’t

used to, say, make him appear at one side of the frame than at the other in

quick succession) and in one strange moment he grows massive wings for no real

reason. It stands out in the mind as it

is the only such moment in the play. It’s not helped by the decision to cover Dixon in bronze body paint

and for him to deliver all his lines in a sing-song manner that quickly begins

to grate.

As

a director, John Gorrie seems at a loss with what to do here with the play,

totally lacking the strong sense of place, narrative drive and visual style

that he brought to Twelfth Night.

This is clear throughout his failure to really exploit the special effects and

editing tricks that TV has available to it. David Dixon’s Ariel disappears into

thin air a few times (usually after a run and jump) and can be seen as a

transparent spirit but that’s about it. He still moves normally (editing isn’t

used to, say, make him appear at one side of the frame than at the other in

quick succession) and in one strange moment he grows massive wings for no real

reason. It stands out in the mind as it

is the only such moment in the play. It’s not helped by the decision to cover Dixon in bronze body paint

and for him to deliver all his lines in a sing-song manner that quickly begins

to grate.

The

appearance of the rest of the sprites hammers home the problem. The spirits are

either operatic singers or painted male dancers in loin clothes who (camp

alert!) move erotically around their fellow actors and the table of food in A4

S1, all the while gurning their various emotions. These extended sequences look

particularly feeble today, so used are we to far better done (and more

interestingly filmed) group dances on Strictly

Come Dancing. These sequences also go on for a quite considerable time (a

good ten minutes throughout the production is given over to singing and dancing

sprites), more than enough to start biting into any viewer’s interest.

The

appearance of the rest of the sprites hammers home the problem. The spirits are

either operatic singers or painted male dancers in loin clothes who (camp

alert!) move erotically around their fellow actors and the table of food in A4

S1, all the while gurning their various emotions. These extended sequences look

particularly feeble today, so used are we to far better done (and more

interestingly filmed) group dances on Strictly

Come Dancing. These sequences also go on for a quite considerable time (a

good ten minutes throughout the production is given over to singing and dancing

sprites), more than enough to start biting into any viewer’s interest.

It’s

a shame because it actually starts rather well with the storm sequence, which

has a filmic quality notably absent from the rest of the production – it’s by

far and away the most exciting and well-filmed segment of the film. On close

inspection, yes, this section is clearly as studio-bound as the rest, but it

looks a hell of a lot better and, despite the camera work being pretty flat,

it’s also visually very interesting. There is a motif throughout the production of

characters standing in close-up at edges of the frame, looking in towards the

rest of the action. This seems designed to suggest a sense of the island being

“full of noises” and an atmosphere of watching. Sadly this visual idea doesn’t

carry across very well into the mood of the film, or in the use of Ariel and

the other sprites (the main watchers) – so maybe it was a directorial flourish

rather than an interpretative idea.

It’s

a shame because it actually starts rather well with the storm sequence, which

has a filmic quality notably absent from the rest of the production – it’s by

far and away the most exciting and well-filmed segment of the film. On close

inspection, yes, this section is clearly as studio-bound as the rest, but it

looks a hell of a lot better and, despite the camera work being pretty flat,

it’s also visually very interesting. There is a motif throughout the production of

characters standing in close-up at edges of the frame, looking in towards the

rest of the action. This seems designed to suggest a sense of the island being

“full of noises” and an atmosphere of watching. Sadly this visual idea doesn’t

carry across very well into the mood of the film, or in the use of Ariel and

the other sprites (the main watchers) – so maybe it was a directorial flourish

rather than an interpretative idea.

The

performances also vary. We should start of course with Prospero himself. Michael

Hordern stepped into the breach as a last minute replacement for John Gielgud

after scheduling prevented the great man from appearing. Hordern gives a lot of

vocal strength to his interpretation, making Prospero into a sort of retired

university don, his weathered features nicely suggesting the years he has spent

in harsh conditions on the island. He also brings some of the sharpness and

testiness of a bitter old man to his interactions with others, as well as a

possessive neediness over Miranda (the sequence in A1 S1 where Prospero effectively

outlines the backstory and constantly asks her to affirm she is listening is

very good). His Prospero is a country gentleman driven to fury against those

who have wronged him, scolding them like a schoolmaster and imperiously ruling

over events with the air of one born to the position. But he also brings a

great little note of sadness at the end of the play, realising that, with the

loss of his staff and the island, he has surrendered everything which made him

unique – it leads in very nicely to the famous final speech, where Hordern

breaks the fourth wall and addresses the viewer directly.

The

performances also vary. We should start of course with Prospero himself. Michael

Hordern stepped into the breach as a last minute replacement for John Gielgud

after scheduling prevented the great man from appearing. Hordern gives a lot of

vocal strength to his interpretation, making Prospero into a sort of retired

university don, his weathered features nicely suggesting the years he has spent

in harsh conditions on the island. He also brings some of the sharpness and

testiness of a bitter old man to his interactions with others, as well as a

possessive neediness over Miranda (the sequence in A1 S1 where Prospero effectively

outlines the backstory and constantly asks her to affirm she is listening is

very good). His Prospero is a country gentleman driven to fury against those

who have wronged him, scolding them like a schoolmaster and imperiously ruling

over events with the air of one born to the position. But he also brings a

great little note of sadness at the end of the play, realising that, with the

loss of his staff and the island, he has surrendered everything which made him

unique – it leads in very nicely to the famous final speech, where Hordern

breaks the fourth wall and addresses the viewer directly.

However,

when it comes to his daughter, I’m not quite sure what he’s worried about to be

honest. Real-life cousins Christopher and Pippa Guard are so lacking in

chemistry that the chances of him undoing her “virgin knot” seem remote to say

the least. Christopher Guard makes nothing of the part of Ferdinand, here an

earnest but terminally dull young man with no sense of character. Pippa Guard

wildly overacts as a simpering and wet Miranda, her performance painfully over-theatrical

in both vocal mannerisms and gestures. Rarely has such a chaste pairing been

seen on screen.

The

shipwrecked lords also give similarly uninspired performances. Derek Godfrey and

Alan Rowe do the best that they can with the complete lack of interpretative

depth given to Antonio and Sebastian. John Nettleton’s Gonzalo is little more

than a silly old buffer. David Waller gives a strikingly poor, disengaged

performance as Alonso. Over-dressed in tights and period detail, the two scenes

concentrating on this group fall totally flat.

However,

when it comes to his daughter, I’m not quite sure what he’s worried about to be

honest. Real-life cousins Christopher and Pippa Guard are so lacking in

chemistry that the chances of him undoing her “virgin knot” seem remote to say

the least. Christopher Guard makes nothing of the part of Ferdinand, here an

earnest but terminally dull young man with no sense of character. Pippa Guard

wildly overacts as a simpering and wet Miranda, her performance painfully over-theatrical

in both vocal mannerisms and gestures. Rarely has such a chaste pairing been

seen on screen.

The

shipwrecked lords also give similarly uninspired performances. Derek Godfrey and

Alan Rowe do the best that they can with the complete lack of interpretative

depth given to Antonio and Sebastian. John Nettleton’s Gonzalo is little more

than a silly old buffer. David Waller gives a strikingly poor, disengaged

performance as Alonso. Over-dressed in tights and period detail, the two scenes

concentrating on this group fall totally flat.

So,

for the first time in this series, it’s the comedy pairings that really work.

Nigel Hawthorne brings an excellent bombastic quality to Stephano. He combines this

with a great playful quality – in A4 S1 he even plays the “I begin to have

bloody thoughts” line with a playful glee, as if revelling in new-found

naughtiness. It’s a performance full of relish at assuming a position of

grandeur and is actually funny – no mean feat in this series, as we have seen.

Andrew Sachs backs him up nicely as Trinculo, although he does seem a little

like an English Manuel. Warren Clarke’s tortured Caliban is a highlight

however, bubbling with resentment in A1 S2 but also moved to tears at

remembering Prospero’s past kindness, a fragile neediness in his character

making his later joyous embracing of Stephano make sense.

So,

for the first time in this series, it’s the comedy pairings that really work.

Nigel Hawthorne brings an excellent bombastic quality to Stephano. He combines this

with a great playful quality – in A4 S1 he even plays the “I begin to have

bloody thoughts” line with a playful glee, as if revelling in new-found

naughtiness. It’s a performance full of relish at assuming a position of

grandeur and is actually funny – no mean feat in this series, as we have seen.

Andrew Sachs backs him up nicely as Trinculo, although he does seem a little

like an English Manuel. Warren Clarke’s tortured Caliban is a highlight

however, bubbling with resentment in A1 S2 but also moved to tears at

remembering Prospero’s past kindness, a fragile neediness in his character

making his later joyous embracing of Stephano make sense.

This

is a decent adaptation of a play that can often come across as slightly flat

production, with many lightly sketched characters. There are some decent

performances, but it’s muddily filmed and rather dull in places and lacks a

real sense of drama. There are some solid performances but nothing outstanding,

although Hordern, Hawthorne and Clarke do some good work. I’m not sure a film

can be really made of this most theatrical of pieces, but I’m certain that a

better fist of it can be made than this production.

Conclusion

Not

going to win any new fans to the play, this ticks all the boxes but does so

with such diligence you can almost picture the director and producer clasping a

clipboard and pencil during filming. Not the worst film, but certainly not the

best.

NEXT TIME: It’s the big one –

Derek Jacobi returns to play the Dane (for what must have been the 700th

time in his life) in Hamlet.

This

is a decent adaptation of a play that can often come across as slightly flat

production, with many lightly sketched characters. There are some decent

performances, but it’s muddily filmed and rather dull in places and lacks a

real sense of drama. There are some solid performances but nothing outstanding,

although Hordern, Hawthorne and Clarke do some good work. I’m not sure a film

can be really made of this most theatrical of pieces, but I’m certain that a

better fist of it can be made than this production.

Conclusion

Not

going to win any new fans to the play, this ticks all the boxes but does so

with such diligence you can almost picture the director and producer clasping a

clipboard and pencil during filming. Not the worst film, but certainly not the

best.

NEXT TIME: It’s the big one –

Derek Jacobi returns to play the Dane (for what must have been the 700th

time in his life) in Hamlet.