First Transmitted 11 January 1981

|

Jeremy Kemp goes wild with envy as Leontes |

Director: Jane Howell

When

I was starting out on this journey through the annals of BBC Shakespeare, this

production of Winter’s Tale was one

which seemed to meet particular ire. In fact, I remember being in a

production of Winter’s Tale myself

almost seven years ago (I played the Clown if anyone is interested) and

discussion with a few other members of the cast turned to film versions of the

play. Sure enough this production was named as being particularly bland, awful

and dull. So this felt like it had a bit of a reputation coming into it. Was

it, in fact, a real low point in the series or was it much misunderstood?

When

I was starting out on this journey through the annals of BBC Shakespeare, this

production of Winter’s Tale was one

which seemed to meet particular ire. In fact, I remember being in a

production of Winter’s Tale myself

almost seven years ago (I played the Clown if anyone is interested) and

discussion with a few other members of the cast turned to film versions of the

play. Sure enough this production was named as being particularly bland, awful

and dull. So this felt like it had a bit of a reputation coming into it. Was

it, in fact, a real low point in the series or was it much misunderstood? Well

to quote Alan Hansen, it was “a game of two halves”. Firstly, with its

incredibly minimalist set and restrained acting, I can see why

people find this production dry and lacking in energy. And I would agree with

them certainly when criticising Acts 4 and

5 which are very bland and forgettable with most of the intended comedy misfiring or

simply dragging on too long (arguably as much a fault of the play). But the

first half of the production, covering Acts 1-3 has a quiet intensity that

actually works very well, creating an atmosphere of paranoia and tension very

effectively. In fact the biggest fault of the production is the darkness

of the first half is undermined by the lightness of the second half.

Well

to quote Alan Hansen, it was “a game of two halves”. Firstly, with its

incredibly minimalist set and restrained acting, I can see why

people find this production dry and lacking in energy. And I would agree with

them certainly when criticising Acts 4 and

5 which are very bland and forgettable with most of the intended comedy misfiring or

simply dragging on too long (arguably as much a fault of the play). But the

first half of the production, covering Acts 1-3 has a quiet intensity that

actually works very well, creating an atmosphere of paranoia and tension very

effectively. In fact the biggest fault of the production is the darkness

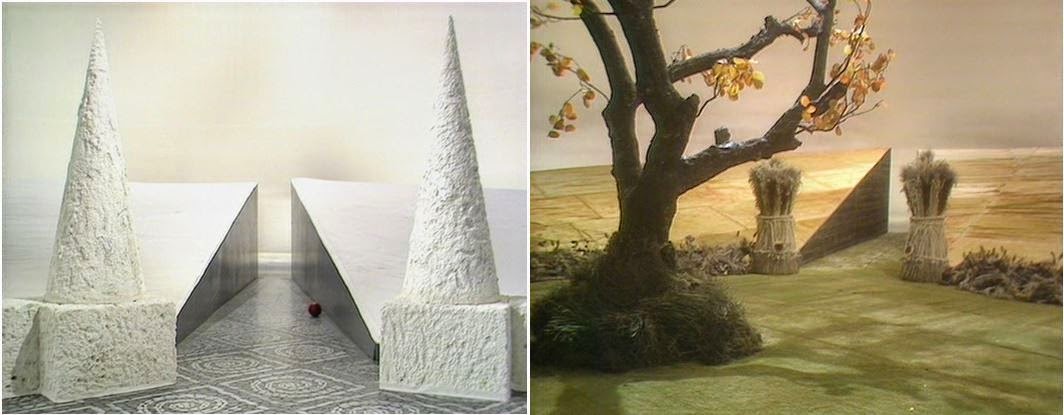

of the first half is undermined by the lightness of the second half.For the style of the production. Jane Howell chooses a deliberately minimalist set, essentially a single rounded stage, centred around a tree (that only flowers in the second half) and full of strange cone shaped objects. Reflecting the mood of the first half of the play, it is kept almost overbearingly white. The second half – the spring section of the play – transforms the same basic location into a lush green countryside. It’s an interesting, non-realist style that uses the limitations of the sound stage and budget to good effect. But it works much better for the first half to be honest – the action of the first half is so constricted and paranoid that the stripped down, stark set marries up very well with the existential crisis that makes up the drama. It’s far less effective when full of colour and dressed to look like a more “real” location.

The

introspective quality of the play’s narrative also allows Howell to make

extensive use of breaking the fourth wall. In a highly effective device,

characters turn towards the frame – often with other characters continuing

conversations or action behind them – and confide their inner thoughts to the

audience. Intriguingly this is not just restricted to obvious asides

or speeches but also for parts of speeches or small individual lines. The

consistent application of this throughout does a great job of making the camera

another character in the drama and allows the actors to develop a lovely

balance between a “public” and “private” face. The device is well enough used

that Howell even allows Fulton’s Autolycus to question it by peeping over

Camillo’s shoulder mid-speech as if wondering who he is talking to.

The

introspective quality of the play’s narrative also allows Howell to make

extensive use of breaking the fourth wall. In a highly effective device,

characters turn towards the frame – often with other characters continuing

conversations or action behind them – and confide their inner thoughts to the

audience. Intriguingly this is not just restricted to obvious asides

or speeches but also for parts of speeches or small individual lines. The

consistent application of this throughout does a great job of making the camera

another character in the drama and allows the actors to develop a lovely

balance between a “public” and “private” face. The device is well enough used

that Howell even allows Fulton’s Autolycus to question it by peeping over

Camillo’s shoulder mid-speech as if wondering who he is talking to.But, as with the set, the effectiveness of this device is restricted to the first half of the production. In fact, it’s hard not to shake the feeling that Howell and the creative team were seized with interest in the idea of making a drama about misdirected envy and family tragedy and got lost once the play moved away from these themes.

These themes are present throughout the first half. Howell makes it clear that, other than some hand holding and affection, there is nothing between Polixenes and Hermione (even if there are suggestions that Polixenes would not be averse to such an arrangement). Leontes’ decision to publically condemn his wife is challenged – there are several effective scenes of courtiers crowding around Leontes in an attempt to moderate his actions – but he remains fanatically fixed on his course of action.

The intensity of the first half of the play is expertly handled, with events piling forward with an unstoppable force. The acting style chosen – remote and restrained – makes the flash points of anger and fury even more effective. At points Howell’s camera focuses in tightly on the faces of the leading characters, but she also allows the frame to be filled with courtiers and trial officials, all pushing their perspective of events with an impassioned urgency. The emotion and pain of the events pours out from the faces of Kemp, Calder-Marshall and Tyzack in particular and the other actors successfully convince with the puzzled bafflement and powerlessness. Combined with the bleak set – which has echoes of Beckett – the whole first half seems to be taking place in some nihilistic world of despair. It’s fantastically effective and expertly done.

The switch occurs from A4 S3. Antigonus’ rather dull speech is left unfortunately intact. The limitations of the setting are displayed in their total failure to create a stormy night (indeed the darker storm backdrop is removed from the frame before the text seems to indicate that the storm has finished). The less said about the famous bear the better – the picture kind of says it all. But it brings back memories of Doctor Who. It’s a failure of directorial imagination to not find a better way - lights, editing, anything, to get a better vision of this on screen.

As noted, nearly all the directorial flourishes are focused on making a cold, claustrophobic atmosphere and none of them carry across effectively to the lighter second half, as the devices are repeated but to dramatically less effect. Even the court reconciliation scenes fail to carry any impact. The introspective underplaying of the first half is continued, but it leads instead to a rather cold response, with Kemp’s Leontes in particular being hard to read. In fact, the entire culmination of the play is almost entirely lacking in a satisfying emotional conclusion – I was completely unmoved by Hermione’s return from the dead, and the dry stale atmosphere runs through all the later court scenes. The sheep shearing and country scenes are complete duds and seem to stretch on forever. It’s a production that actually seems undermined by being uncut – you feel Howell would have been happier producing something closer to two hours in length.

The

second half is also cursed by containing the weaker performances. Robin Kermode

and Debbie Farrington make particularly unengaging and dull young lovers. Paul

Jesson does provide plenty of energy as the Clown but Rikki Fulton’s Autolycus

is less successful, never convincingly showing the selfish, sinister

quality behind the joviality. Robert Stephens looks the worse for wear as

Polixenes, but he does give him a lecherous quality that works well in Act 1.

As mentioned, Kemp’s performance in Act 5 falls slightly flat.

The

second half is also cursed by containing the weaker performances. Robin Kermode

and Debbie Farrington make particularly unengaging and dull young lovers. Paul

Jesson does provide plenty of energy as the Clown but Rikki Fulton’s Autolycus

is less successful, never convincingly showing the selfish, sinister

quality behind the joviality. Robert Stephens looks the worse for wear as

Polixenes, but he does give him a lecherous quality that works well in Act 1.

As mentioned, Kemp’s performance in Act 5 falls slightly flat.Which is a shame as Kemp brings a great deal of emotion and power to Leontes in the first half of the production. Bubbling with tension and paranoid fury but also somehow consciously aware that he is on a path of self destruction, Kemp is a whirlpool of depression and self loathing, but a man convinced he has been wronged and determined to let justice be done though the heavens fall. His Leontes is a man who convinces himself so thoroughly that his suspicions snowball from hand-holding to a lifetime of betrayal. He is a man for whom emotions are at the fore – he practically weeps with an et tu pain when Camillo questions him – and who will not be shaken by anyone. Howell repeatedly shows Kemp at the centre of a whirligig of protests and Kemp demonstrates that his heartbroken pain will not stop him from doing what has to be done. It’s a powerful performance but I think slightly one-note – largely because I think Kemp struggles to introduce any new elements to it in the second half of the play. He nails the pain and rage of the first part but fails to bring the same depth to the second half.

A lack of depth is missing from most of the performances, and I think this ties into a slightly black and white interpretation of the characters. Margaret Tyzack is a terrific actress and she really nails the force of character and the strength of will of Paulina but the character seems the same throughout – even in the second part, there does not seem much change in her corrective tone as ifi she has been telling Leontes off for 16 years. Anna Calder-Marshall also gives a moving performance as Hermione, a blameless woman in torment, but that is basically the only note she is called upon to deliver. She does so expertly, but there is no room in the concept given to her to demonstrate any light or shade. David Burke gives perhaps the most shaded and multi-facted performance as Camillo, who like Leontes regretfully will do what he sees as right, but slowly introduces a greater shade of selfishness into his actions as age combines with a longing to see Bohemia (this change of character perhaps explains why he is the only character who seems to age in the play).

This

is all part of a trend. It’s half a great adaptation but

just falls short throughout. There are some excellent ideas – the

set, the directing style, several moments of the acting, the tension – but it

fails to push these ideas to the next level. All the leading

performances – Kemp, Calder-Marshall, Tyzack – fail to develop and change from

the first half to the second. Once the play breaks from the intensity of the

build up to the trial into the rest of the action, the energy of the acting and

directing disappears as if the spell is broken. All the structure and ideas

work for that one set-up, all the performances are geared towards it, even the

aesthetic only works for it. Once we break into the lightness and the comedy

the production falls apart.

This

is all part of a trend. It’s half a great adaptation but

just falls short throughout. There are some excellent ideas – the

set, the directing style, several moments of the acting, the tension – but it

fails to push these ideas to the next level. All the leading

performances – Kemp, Calder-Marshall, Tyzack – fail to develop and change from

the first half to the second. Once the play breaks from the intensity of the

build up to the trial into the rest of the action, the energy of the acting and

directing disappears as if the spell is broken. All the structure and ideas

work for that one set-up, all the performances are geared towards it, even the

aesthetic only works for it. Once we break into the lightness and the comedy

the production falls apart.This is not the terrible production you might be led to believe, but it is a missed opportunity. If the elements had come together better – or even if the play had been reduced in length and the second half cut down significantly – then the production as a whole would have been a great success. As it is, this offers one prolonged sequence of excellence but then a deflating disappointment, like watching a hot air balloon fly, crash to the ground and then all the air slowly leak out over an hour and fifteen minutes. Such a shame.

Conclusion

The ideas are there and many of the performances are also very good. The directing style and aesthetics are very interesting and work in tandem with the text very well to create a particular mood and effect. But A3 S4 onwards feels botched, disengaged and low in energy – particularly compared to what has gone before – and the end result is a disappointment. Kemp, Tyzack, Calder-Marshall and Burke in particular are very good, but even they seem to dwindle in the second half and fail to completely change the pace away from tragedy to relief. A near miss, but a miss – but it lays good groundwork for staging ideas that would be explored later in the series.

NEXT TIME: Jonathan Pryce rages against the ingratitude of his fellows as Timon of Athens.

No comments:

Post a Comment